“Dali couldn’t be filmed”: the surprising story of Hitchcock’s missing storyboards – found at a jumble sale | Cinema

ANDIt’s Los Angeles, the early 1970s, and critic John Russell Taylor is driving around the San Fernando Valley, checking out the goods offered at various sales. Locals often leave their garbage on their lawns in hopes of collecting some cash. Less common, however, is a prize that Taylor spots in one yard: a series of storyboards from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 film Spellbound, a thriller about a psychoanalyst starring Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck.

Taylor recognizes them immediately. He is a Hitchcock scholar who will write an authorized biography of the director. Upon closer inspection, he notices something else: one of the panels depicts a famous film dream sequence, and it seems to have been drawn by a different artist to the others; a world-famous surrealist who was hired when the sequence was first conceived as a 20-minute interlude rather than the three-minute segment it ultimately became. Among the stack of nine storyboard drawings Taylor bought that day was one that was most likely drawn by Salvador Dalí himself.

“I don’t remember how much I paid, but I think it was $50 for the piece,” Taylor says when I meet him at his home, a modest terraced house on the outskirts of London, which once inside reveals a cornucopia of art. Nine Hitchcock panels are proudly displayed above the living room fireplace, with a Dalí panel taking center stage.

At the time of the purchase, Taylor met Hitchcock for lunch every week. He says the director assured him it was the original Dalí, recalling how the surrealist had hastily corrected some angles with watercolors. Hitchcock also confirmed that the remaining storyboards were from a series created by art director James Basevi, who was asked to condense Dalí’s ambitious vision into something more traditional (and certainly cheaper to film). “You can see some of Hitch’s sketches in the margins,” Taylor notes, showing me the panels.

The story of the director and his storyboards is a fascinating one, as told in the new book Alfred Hitchcock Storyboards by Tony Lee Moral, who is also at Taylor’s house today. While other directors might sketch very rough scenes as a guide to their films (or not bother with them at all), Hitchcock was meticulous, creating painstakingly drawn images that could be transferred to the screen almost like a photocopier. In fact, Hitchcock sometimes claimed that storyboarding was his primary creative responsibility and that he considered the directing process to be a dunce’s job, so boring that he barely bothered to look into the viewfinder.

“He always said anyone could have directed his movies,” Taylor laughs. “Because he had it all planned out in his head beforehand.” He recalls their first meeting in London in 1972, when Hitchcock was filming a river scene for Frenzy. “It was a freezing middle of winter and Hitch said, ‘If it gets any colder, I’ll just call.’ Of course, it is not true that anyone could have stepped in and directed. I saw him add and change things a few times while filming. But that’s what he liked to say anyway.

The detailed storyboard also helped Hitchcock avoid something he hated: cliché. When he made Shadow of a Doubt, he wanted to break his film noir from the stereotypes of dark alleys and lurking strangers, so his storyboards reflected a radical use of light and shadow. Meanwhile, the sketches for Vertigo show the action taking place from the character’s point of view, a perspective so difficult to capture on camera that Hitchcock had to create a new lens effect especially for it.

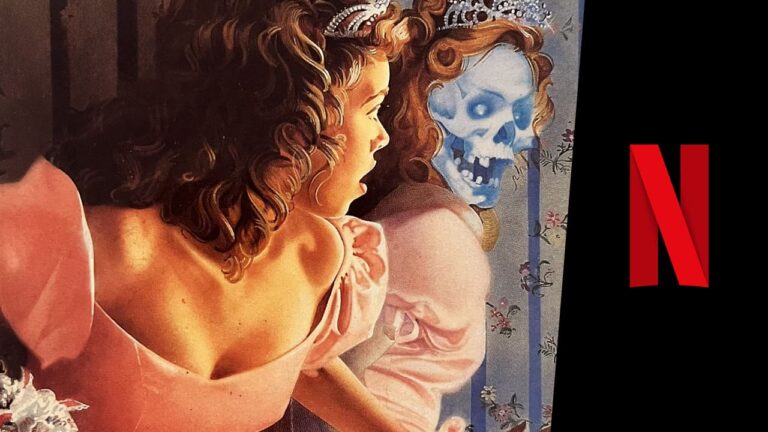

His aversion to clichés was fully demonstrated in the Spellbound dream sequence, which played a key role in the film’s plot. While other directors liked to rub Vaseline on the camera lens to create hazy night visions, Hitchcock aimed to create something as bright and distinct as our most vivid dreams. To achieve this, he paid Dalí the princely sum of $4,000 to design the film’s unique set.

“Hitch was smart,” Moral says. “He knew that Dalí was a big name who would make the film worth promoting.” And Dalí jumped at the opportunity, desperate to break into Hollywood. He had already made several art films with Luis Buñuel (Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or) when he was commissioned for Spellbound, and shortly thereafter began work on Destino, an animated short film for Disney that was eventually released in 2003.

The problem was that Dalí’s ideas for Spellbound were small too unique. Among other things, his storyboards depicted Bergman transforming into a statue, which then disintegrated into ants. “It was basically unsuitable for filming,” says Moral.

This was certainly the opinion of producer David O Selznick, who became so concerned about the costs that he considered scrapping the film altogether. Finally, he asked Basevi to create a more pragmatic version, still based on Dalí’s sketches. “I would say Dalí played a big role in the finished sequence, but from a certain distance,” Taylor says.

The artist may have been disappointed – his final credit was “A Dream Sequence Based on the Designs of Salvador Dalí” – but the finished film certainly lived up to Hitchcock’s vision for a dazzling sequence.

As his friendship with Hitchcock blossomed, Taylor lived and taught in Los Angeles. In fact, Hitchcock’s personal assistant, Peggy Robertson, once told Taylor that Hitchcock saw him as the son he never had. “I was the right age and British,” Taylor says. “And as Cary Grant once told me, at least I knew what Lucretia Allsorts were!”

Taylor recalls the jokes that made Hitchcock’s reputation: like the time he brought a live horse into the dressing room of his actor friend Gerald du Maurier. “They were fantastic, not cruel,” he says. Although I’m not sure you could say that it was around the time Hitchcock shackled one of his film technicians in the studio overnight, secretly dosing him with laxatives before a night out. “It doesn’t sound like the nicest joke, he shit himself last night,” Taylor admits. “But I talked to people who worked on the movie and they said they didn’t like this person, and it worked out well for them.”

Hitchcock, of course, had a reputation darker than mere jokes. In her 2016 memoir, Tippi Hedren claimed that the director committed sexual assault while she was working on The Birds and Marnie.

According to Taylor, Hitchcock described himself as “the shyest, most timid man in the world”, someone who ate dinner with his family in a special enclave of restaurants so as not to be noticed. He also had a cynical view of friendship, once jokingly telling Taylor that he only had two friends: “One of them is the meanest man in the world, and the other one would stab me in the back if he so much as looked at me.” Taylor notes that almost all of Hitchcock’s close relationships were with women, “so I think I had an advantage in that.”

One thing he is adamant about is that Hitchcock was truly special. He tells me that the standard for the director was to shoot a given scene several times – a long shot, a close-up and a medium close-up, so the producer had various editing options. But Hitchcock hated it when people interfered with his films. Perhaps that’s another reason he relied so heavily on his storyboards: it meant he could capture exactly what he wanted and nothing more. This way, even an interfering producer like Selznick would have difficulty tampering with the final result.

“He always found ways to have complete control over his films,” Taylor says. “He wasn’t a fool, he was Hitchcock.”